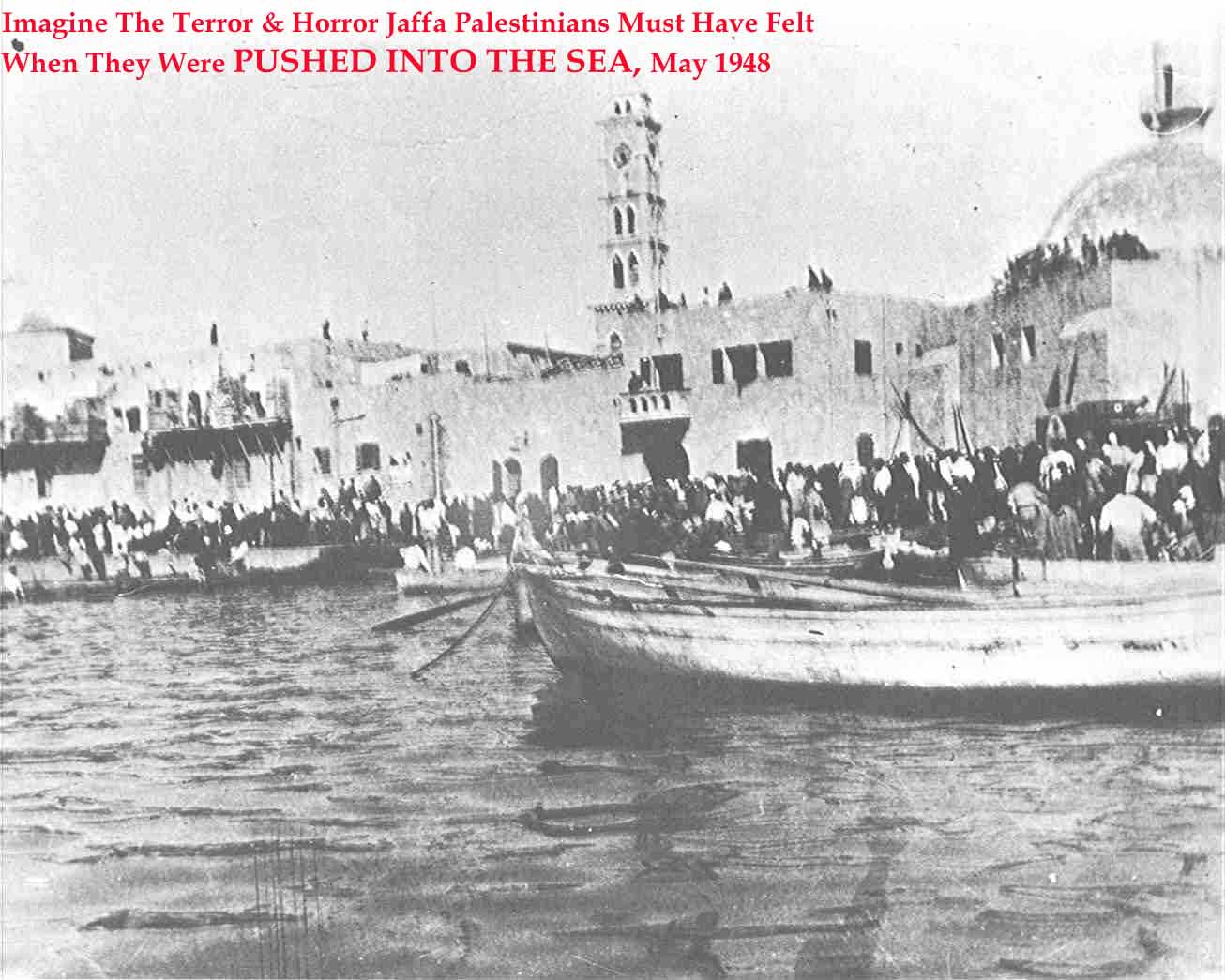

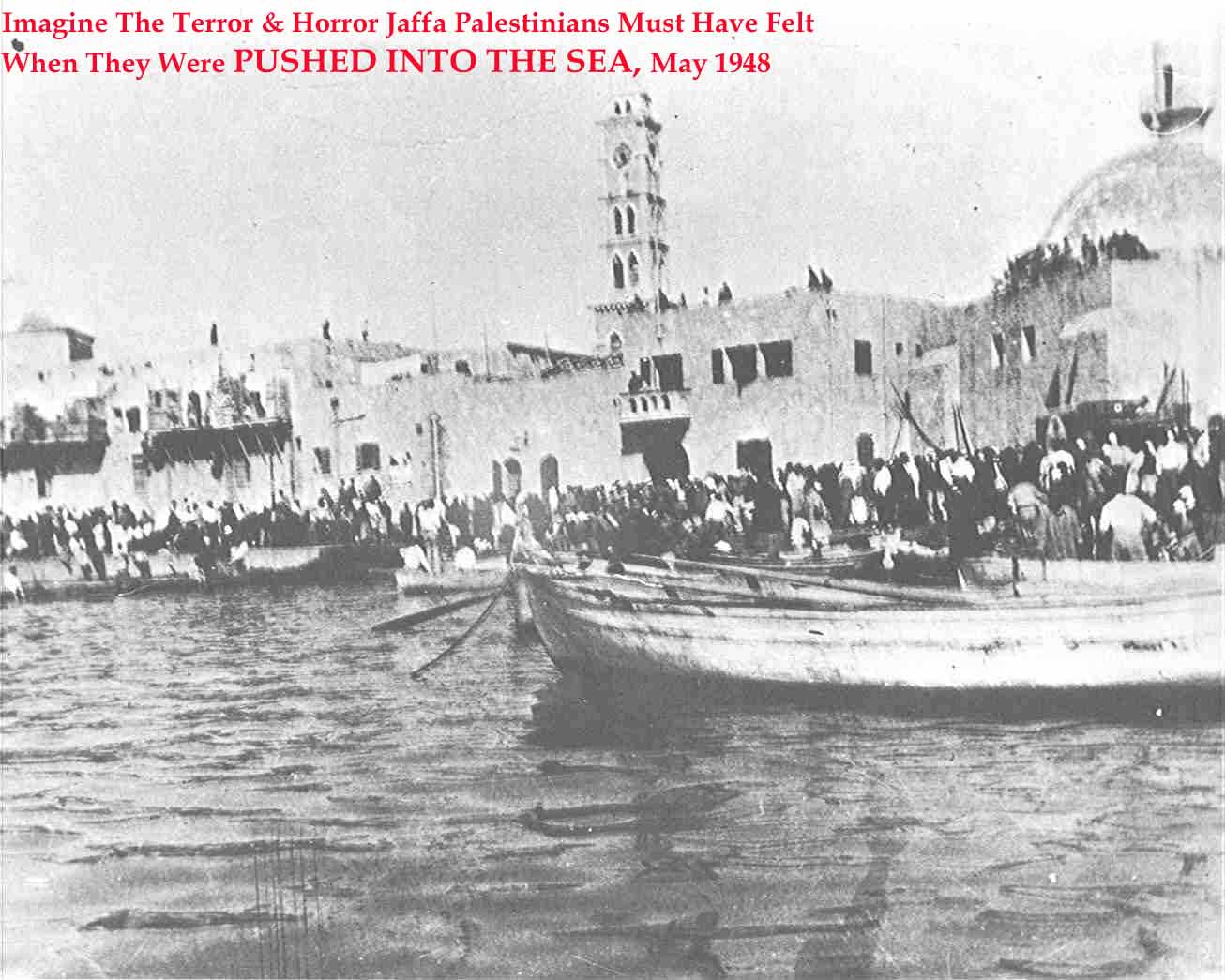

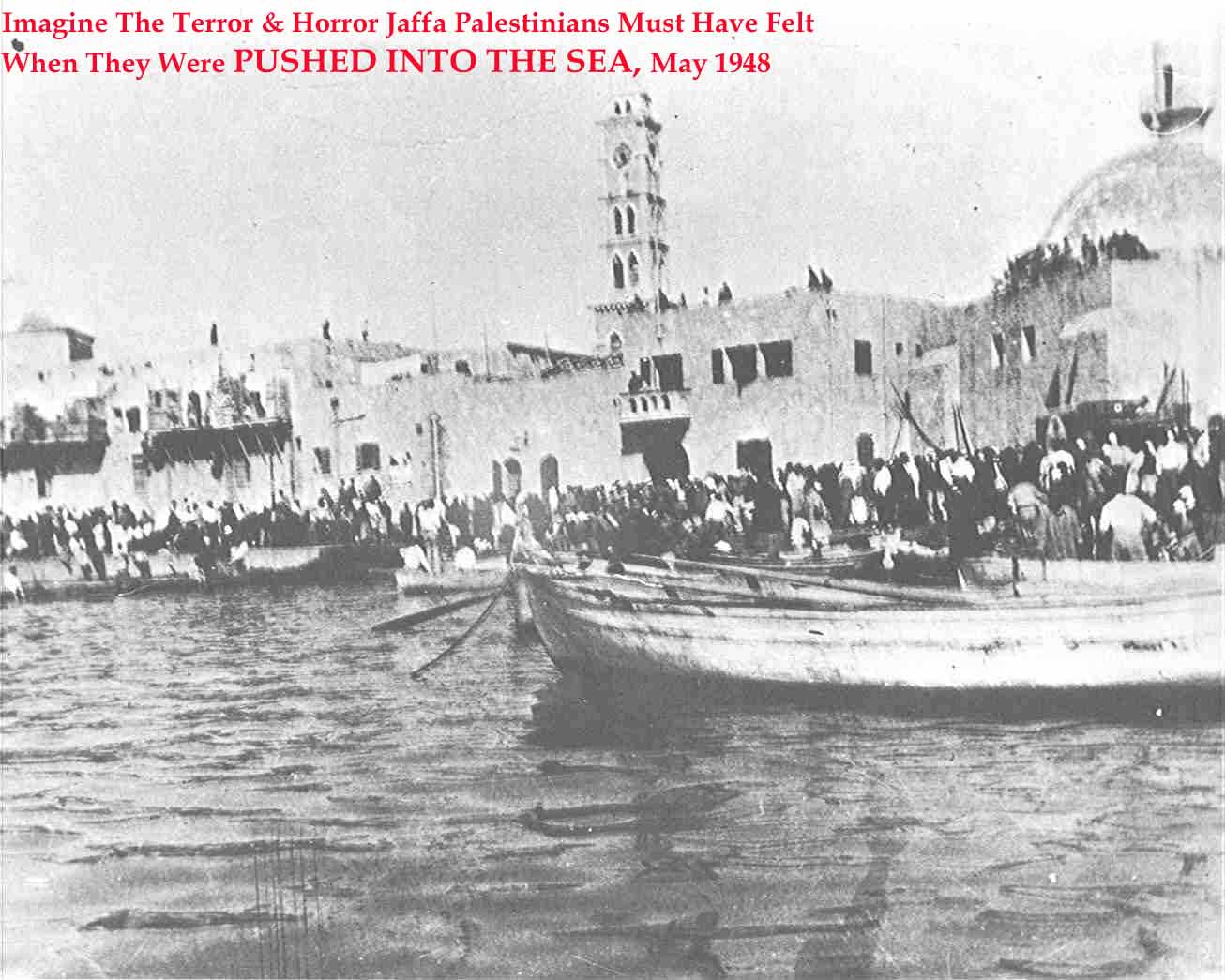

Remind us, please: who shall push who into the sea? Jaffa May 1948, Palestinians were being pushed into the sea by Zionist Jewish forces.

Remind us, please: who shall push who into the sea? Jaffa May 1948, Palestinians were being pushed into the sea by Zionist Jewish forces.1. Language as a battlefield of power

Antonio Gramsci argued that domination endures not through force alone but through cultural hegemony—the quiet shaping of common sense so that the worldview of the powerful feels natural. Language, symbols, and naming become instruments of consent.

In Palestine and the wider Levant, we can watch this process unfold in real time: familiar words—Sahyoun, Magen David, Nakba, Shoah, even the names of villages—have been pulled out of their shared pasts and reassigned to new ideological masters. Each change marks an episode of hegemony at work.

2. The “Catastrophe” that split in two

Faluja-Gaza, 1949, Ethnically Cleansed Palestinians on their way to Hebron

Faluja-Gaza, 1949, Ethnically Cleansed Palestinians on their way to Hebron

Before 1948, Jewish writers called their calamities ha-katastrofah or ha-ason, borrowing the European “Catastrophe.” For example, here's how Hannah Arendt used the term "Catastophe" when she compared Zionism to Shabbatai Tzvi's catastrophic messianic movement, and here's Albert Einstein using the term catastrophe in the context of the Zionist Jews who committed the massacre at Deir Yassin on April 10th, 1948.

After 1948, Palestinians adopted its Arabic twin, al-Nakba, to describe their dispossession.

The Jewish world then elevated Shoah (a biblical word for “desolation”) as the sacred, exclusive term for the Holocaust, and the ordinary Catastrophe quietly disappeared.

Two cultures, once sharing a common vocabulary of tragedy, now occupy separate semantic realms. That bifurcation is a textbook act of hegemony: by fixing the meaning of suffering, each community secured moral authority and erased the other’s claim to the word.

3. From shared symbols to nationalist property

Residence of al-Ramla being ethnically cleansed based on the orders from Rabin; July 1948

Residence of al-Ramla being ethnically cleansed based on the orders from Rabin; July 1948For centuries, Sahyoun —Zion — was a neutral toponym across Semitic languages, and the six-pointed star (the Seal of Sulayman) decorated mosques, khans, and homes as a charm of protection.

When political Zionism claimed both as its banners, Arab societies relinquished them.

Families renamed themselves; artisans stopped carving the star; schoolbooks omitted it.

Gramsci would call this a reorganization of cultural common sense—the subaltern majority internalizing the notion that certain signs “belong” to the hegemon.

4. The self-policing of speech

Browse hundreds of pictures depicting Palestinian culture & folklore

Browse hundreds of pictures depicting Palestinian culture & folkloreNo one decreed these erasures. People adopted them to avoid stigma or to signal modern belonging.

That is the subtlety of hegemony: it works through consent and self-censorship, not coercion.

A Damascene family dropping Sahyoun from its surname, or a Palestinian mason disguising a hexagram as a floral rosette, is not obeying a law; he is negotiating survival inside a linguistic order already defined by others.

5. Renaming the landscape

Colonial and nationalist administrations continued the pattern.

Mandate and post-1948 maps replaced old village names with new Hebrew or Arab ones.

The practice mirrors Gramsci’s notion that each ruling bloc builds a new historical bloc of meaning—a coherent narrative that naturalizes its territorial claims.

Renaming geography converts possession into common sense.

6. Counter-hegemony: remembering the shared lexicon

Browse hundreds of pictures depicting Palestinian culture.

Browse hundreds of pictures depicting Palestinian culture.Gramsci also envisioned resistance through counter-hegemony—reclaiming the cultural tools that power had privatized.

Rediscovering that Bayt al-Maqdis descends from Beit ha-Miqdash, that the “Star of David” was once the “Seal of Solomon,” or that Sahyoun belonged to every tongue of the Levant, is such an act.

It reopens the suppressed continuity between communities and challenges the assumption that symbols must serve exclusive flags.

7. Reflection

The story of how Catastrophe, Sahyoun, and the six-pointed star “jumped horses” is not merely about etymology.

It reveals how power colonizes language to consolidate identity and erase shared memory—and how ordinary people, seeking safety, reproduce that erasure until it feels natural.

Gramsci reminds us that hegemony depends on forgetfulness; to remember is to resist.

Every time an old inscription bearing the Seal of Solomon surfaces on a Palestinian doorway, or a family quietly keeps the name Sahyoun, the deeper truth returns:

These words and symbols were collective long before they were claimed by any nation.

Remind us, please: who shall push who into the sea? Jaffa May 1948, Palestinians were being pushed into the sea by Zionist Jewish forces.

Remind us, please: who shall push who into the sea? Jaffa May 1948, Palestinians were being pushed into the sea by Zionist Jewish forces. Remind us, please: who shall push who into the sea? Jaffa May 1948, Palestinians were being pushed into the sea by Zionist Jewish forces.

Remind us, please: who shall push who into the sea? Jaffa May 1948, Palestinians were being pushed into the sea by Zionist Jewish forces.

Post Your Comment

*It should be NOTED that your email address won't be shared, and all communications between members will be routed via the website's mail server.